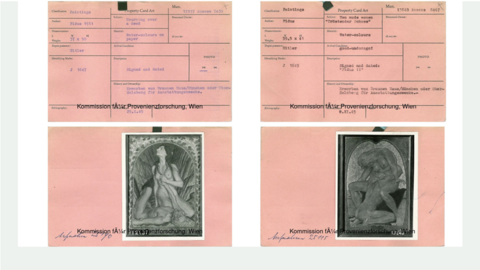

Hugo Höppener, better known by his pseudonym Fidus (1868 – 1948), was a leading figure of the German Life Reform and Jugendstil movements. Such works as his “Totenklage” (1910) and “Tröstender Schoß” (1911) are deeply rooted in mystical symbolism. Both works not only embody themes of grief and comfort but also suggest a subtle, almost erotic relationship between the figures in them, insinuating both physical and spiritual healing.

Blog

Fidus – Artist between Life Reform Movement and National Socialism

![“Fidus, Totenklage [Lamentation of the Dead] (1910) and Tröstender Schoß [Comforting Lap] (1911)“ “Fidus, Totenklage [Lamentation of the Dead] (1910) and Tröstender Schoß [Comforting Lap] (1911)“](/sites/provenance-research.hessen.de/files/styles/crop_image_style_16_9_xs/public/2025-06/test.png?itok=lEAkysFD)

![Fidus in his studio in Woltersdorf in the mid-1930s. Behind him hangs his Tröstender Schoß [Comforting Lap]. Fidus in his studio in Woltersdorf in the mid-1930s. Behind him hangs his Tröstender Schoß [Comforting Lap].](/sites/provenance-research.hessen.de/files/styles/crop_image_style_16_9_xs/public/2025-06/123.png?itok=KOPXdh7J)

In his art Fidus propagated a return to nature, spiritual renewal, and a healthy lifestyle. Yet despite his hope that the National Socialist regime would share his spiritual, nature-oriented ideals, many National Socialists rejected both his art and his philosophy of life. The artist was an early member of the Reich Chamber of Culture and constantly sought proximity to the new centres of power: he repeatedly requested financial support and permission to participate in exhibitions. He even completed a “Portrait of the Führer”; however his pacifist and mystical views were in contradiction to National Socialist ideology.

From Fidus to Bormann

Faced with financial difficulties in the late 1930s and early 1940s, in July 1942 Fidus sold 18 of his pictures to the Munich antique and art dealer Guenther Koch (Neueutherstrasmse 15, Munich) for 4,000 Reichsmarks. That same year these works were acquired by Martin Bormann (1900 – 1945), Reich Minister and confidant of Adolf Hitler (1889 – 1945). Bormann was an important player in National Socialist cultural politics and displayed art works that reflected the NSDAP’s ideology in his official residence’s reception rooms in the Rudolf Heß Reich Settlement in Pullach near Munich. Bormann was particularly notorious for collecting art works that mirrored the NSDAP’s “Nordic” or “Germanic” values.

In the Munich Central Collecting Point

After the Second World War ended and the US Armed Forces occupied the Rudolf Heß Reich Settlement, many of Bormann’s possessions, including the artworks, were confiscated and brought to the Central Collecting Point in Munich, that had been set up by the Allies to secure artworks and objects of cultural value, document them, and return them to their rightful owners.

The Mauerbach Sale 1996

The Munich CCP closed its doors in 1951, and in January 1952 over 900 objects were transferred from Munich to the salt mines at Bad Aussee in Austria, thus becoming the responsibility of the Austrian federal government. It is unclear why this location was chosen; probably the decision was based on the assumption that the artworks had been confiscated or otherwise expropriated in Austria during the National Socialist period. Only later did it turn out that a large portion of the works originated from Germany.

Shortly afterwards the pictures by Fidus were conveyed with many other artworks to monastery Mauerbach near Vienna, where they were stored until the mid-1990s. After giving some advance notice, it was decided to auction off all unclaimed objects to the benefit of victims’ organisations. To this end the works were transferred to the Federal Association of the Jewish Community in Austria for further processing.

On 29 and 30 October 1996, Christie’s auction house organised the sale of a total of 1,045 catalogue items in the MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna. The auction raised some 120 million schillings (8 million US dollars), that was used to benefit victims of National Socialist persecution based on ethnicity, religion, or political affinity.

The Mauerbach Controversy

The Mauerbach Sale became a subject of controversy. Critics claimed that the auction meant that the artworks were for ever lost to the descendants of the original owners and that beforehand insufficient research had been conducted. Yet others saw the auction as a pragmatic solution since after decades had passed either no specific heirs existed anymore or else they could be found only with difficulty. Beyond this, the auction functioned as a catalyst for a wider discussion in society and the research world on restitution and reappraising National Socialist theft of artworks. In particular the unresolved provenance of the works raised questions concerning the responsibility of the art market, museums, and politicians to engage more responsibly with determining the provenance of such objects and to develop standard procedures for dealing with looted art.

Both of Fidus’s pictures were auctioned in the MAK and achieved much higher prices than previously estimated. “Tröstender Schoß“ [Comforting Lap] went to an art dealership in Hanover, whence it was acquired by Ferdinand Wolfgang Neess. “Totenklage“ entered the Parisian art market, where in 2013 it was also bought by Herr Neess. Both pictures were donated to the Museum Wiesbaden in 2017.

Provenance and Responsibility

The provenance history of Fidus’s “Totenklage“ and “Tröstender Schoß“ reveals the complex relationships between art, politics and history in the 20th century—from the prints’ creation in the context of the Life Reform movement, via their instrumentalization by National Socialist cultural politics, to their appearing in the collection of a state museum. The journey of these works through many hands—from Fidus via Martin Bormann to the Allies and the ensuing Mauerbach auction—raises key questions concerning contemporary responsibility and the appropriate reappraisal of cultural assets.

The “Mauerbach Sale” and the two works’ later donation to the Museum Wiesbaden underline the continuing relevance of provenance research and the need to critically examine an artwork’s origins—especially when objects whose provenance has not been thoroughly examined are accepted as donations by museums.

Larissa Engler