That the histories of works no longer in a museum’s collection may still be relevant for provenance research is demonstrated by this Max Slevogt painting, part of the Wiesbaden Gemäldegalerie’s inventory from 1927 to 1940.

Given in Exchange

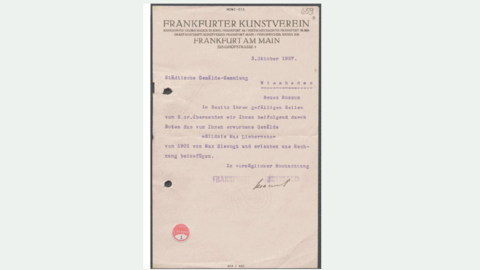

The “Portrait of Herr Deinhardt” by Simon Meister and “Rest before an Inn in a Southern Landscape” by Johannes Lingelbach have been in the Museum Wiesbaden’s collection since March 1940. Both works have been the subject of provenance research. Whereas the provenance of the Lingelbach painting has yet to be fully clarified, we can almost certainly rule out Simon Meister’s work’s being expropriated as the result of National Socialist persecution. Since the two works were acquired together in exchange for a painting by Max Slevogt from the Wiesbaden Gemäldegalerie’s inventory, an important focus of research has been on reconstructing the context in which the two paintings were acquired and thus also on the biography of the Slevogt painting given in exchange.

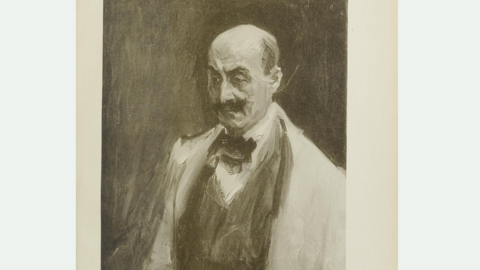

The exchange was effected with the Wiesbaden art dealer Wilhelmine Heinemann Ww., who in March 1940 received the “portrait of the Jewish painter Max Liebermann, painted by Slevogt” as of equivalent worth to the two aforementioned paintings. As we can further learn from Hermann Voss’s communication to the city mayor, authorising the exchange, “The picture, whose very subject precludes its being displayed, had no particular [sic] artistic value, since it is also hardly characteristic of Slevogt’s work.”

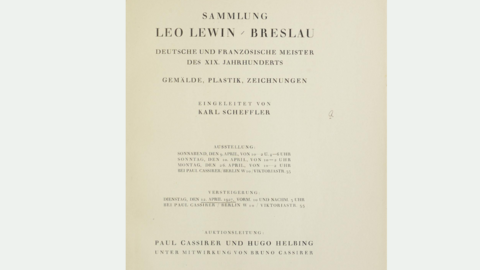

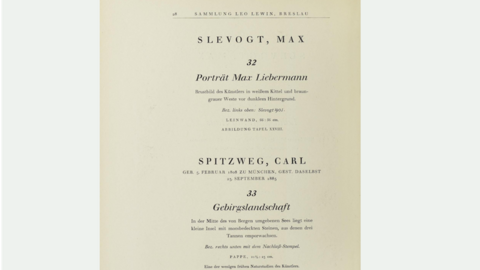

The painting by Slevogt, signed and dated 1901, had previously belonged to the Breslau merchant and art collector Leo Lewin (1881 – 1965). In financial straits, Lewin was forced in April 1927 to offer a part of his collection—including the “Portrait of Max Liebermann”—at auction by Paul Cassirer and Hugo Helbing in Berlin (figs. 1, 2, 3).