The Wella collection at the HLMD

In 2013, when the company’s museum was liquidated, the Wella collection was transferred almost in its entirety to the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt and distributed among the various collections in this universal museum. The over one thousand objects in the graphics collection’s inventory are currently the focus of a project by the Central Office for Provenance Research Hesse, in the course of which the objects’ acquisitional contexts are to be examined for possible expropriation resulting from National Socialist persecution. Although the Wella collection was assembled in the post-war years, for many years neither art dealers nor collectors inquired who were the former owners of a particular object and through whose hands it had passed.

Examining the works on paper from the Wella Collection for possible illegal expropriation is an important step—one that also helps us to learn more about the objects’ biographies, the collection’s context, and the people who were involved in its composition.

From hair tulle to perm to art—the Ströher family and the Wella museum

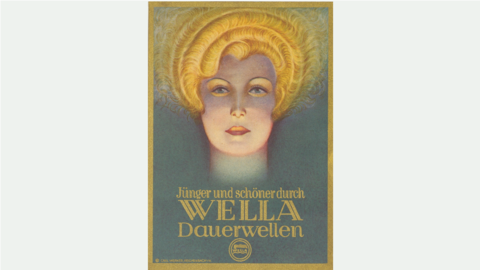

The Wella brand is today world famous. But few people know that from 1952 to the early 2000s the Wella company built up a wide-ranging museum of over 3,000 objects at its Darmstadt headquarters.

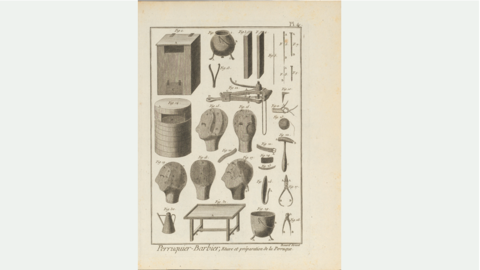

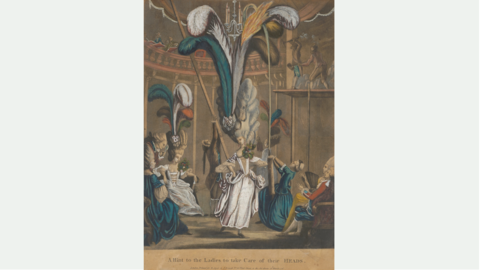

In 1880 in Rothenkirchen (Vogtland), the hairdresser and wigmaker Franz Ströher (1854-1936) opened a hair tulle manufactory, thus laying the foundation stone of the Wella company that, under his sons Karl (1890-1977) and Georg (1891-1964), was to become an international supplier of hairdressing requisites. When the company later settled in Darmstadt, it put together a collection of unique historical and cultural interest in the Wella museum—an institution initiated by Karl und Georg Ströher and open to the general public. The museum’s aim was nothing less than to document the cultural history of the hairdresser’s art and beauty and body care.