Blog

Provenance Research Day

An important goal of provenance research into cultural assets looted as a result of National Socialist persecution is to establish as accurately as possible an artwork’s changes in ownership between 1939 and 1945.

A lack of source records sometimes makes it impossible to determine absolutely the provenance of an object during the National Socialist era, and consequently theft as a result of National Socialist persecution cannot be discounted. But even in such cases, provenance research can contribute important information on the history of collections and their objects.

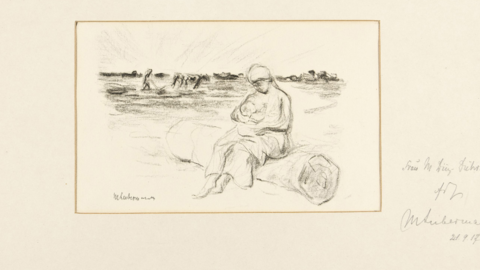

The drawing depicts a mother holding a child and sitting on a log. In the background we can see a broad landscape. A farmer guides a plough pulled by oxen over a field. The drawing is signed in the bottom left-hand corner with “M. Liebermann.”

After its entry into the museum’s collection in 1980 as a gift of Rose and Friedrich Klein, the drawing was initially not inventoried; assignation, year of creation, and technique were neither established nor known. During research into its provenance, on inquiry the Max Liebermann Archive was able to confirm that the drawing was indeed from the hand of the artist and to establish a date of 1917. As the paper restorer of the Museum Wiesbaden was able to determine, Max Liebermann used black chalk on vellum paper to create the drawing. A first clue as to its origin was provided by two inscriptions on its former passe-partout: “Frau M. Diez-Dührkoop” and “M. Liebermann, 21.9.1917.” The painter had dedicated his work to the well-known German photographer Minya Diez-Dührkoop (1873–1929).

Many artists of Modernism had their portrait taken by the Hamburg photographer—Max Liebermann several times. As documented by the painter’s surviving letters, this drawing was a present of Max Liebermann to Minya Diez-Dührkoop. In gratitude for prints she had created in July of 1917, Max Liebermann allowed her to choose a drawing from his studio. Minya Diez-Dührkoop’s reputation as a photographer extended beyond Hamburg. In 1919 the photographer became a founding member of the professional German Photographers’ Association; she participated in the cultural life of Hamburg and collected contemporary art. From 1910 she was a passive member of the artist group “Die Brücke” [The Bridge]. It is interesting that the surviving portraits by Minya Diez-Dührkoop often featured mothers with children, and this is probably why she selected this drawing of a mother nursing her child.

Many artists of Modernism had their portrait taken by the Hamburg photographer—Max Liebermann several times. As documented by the painter’s surviving letters, this drawing was a present of Max Liebermann to Minya Diez-Dührkoop. In gratitude for prints she had created in July of 1917, Max Liebermann allowed her to choose a drawing from his studio. Minya Diez-Dührkoop’s reputation as a photographer extended beyond Hamburg. In 1919 the photographer became a founding member of the professional German Photographers’ Association; she participated in the cultural life of Hamburg and collected contemporary art. From 1910 she was a passive member of the artist group “Die Brücke” [The Bridge]. It is interesting that the surviving portraits by Minya Diez-Dührkoop often featured mothers with children, and this is probably why she selected this drawing of a mother nursing her child.

The drawing comes from one of Max Liebermann’s sketchbooks, as may be seen from the drawing’s torn-off left edge. It was probably created in 1917, whereby Max Liebermann here takes up motifs from his own earlier work. The representations of the nursing mother and the ploughing farmer thus stem from one of his sketches for a portrayal of spring as part of an annual cycle that he executed in 1898 to adorn Altona town hall. Whether the drawing remained in the photographer’s possession until her death in 1929 cannot be ascertained. To date it is also unclear when Rose and Friedrich Klein acquired the work. It is remarkable that the drawing’s passe-partout frame has accompanied it since 1917, for without Max Liebermann’s dedication thereon, the history of the drawing’s provenance could not have been told.

Conclusion:

In order to determine an art work’s provenance, researchers need some kind of starting point—be it written sources such as purchase documents, correspondence, etc., or clues such as this dedication. The more well-known an artist is, the greater the chances that his or her work has already been researched. There exists a multivolume catalogue raisonné of Max Liebermann’s paintings, as well as an edited critical edition of his letters—both are important secondary sources for provenance research. Even though the provenance of the drawing for the period 1933 to 1945 could not so far be definitively established, the research conducted nevertheless yields valuable information and insights on the object’s biography.

Miriam Olivia Merz